We are open May 6th - October 8th 2022. Please book directly with us via our website! We look forward to welcoming you at our beautiful place on Cape Cod.

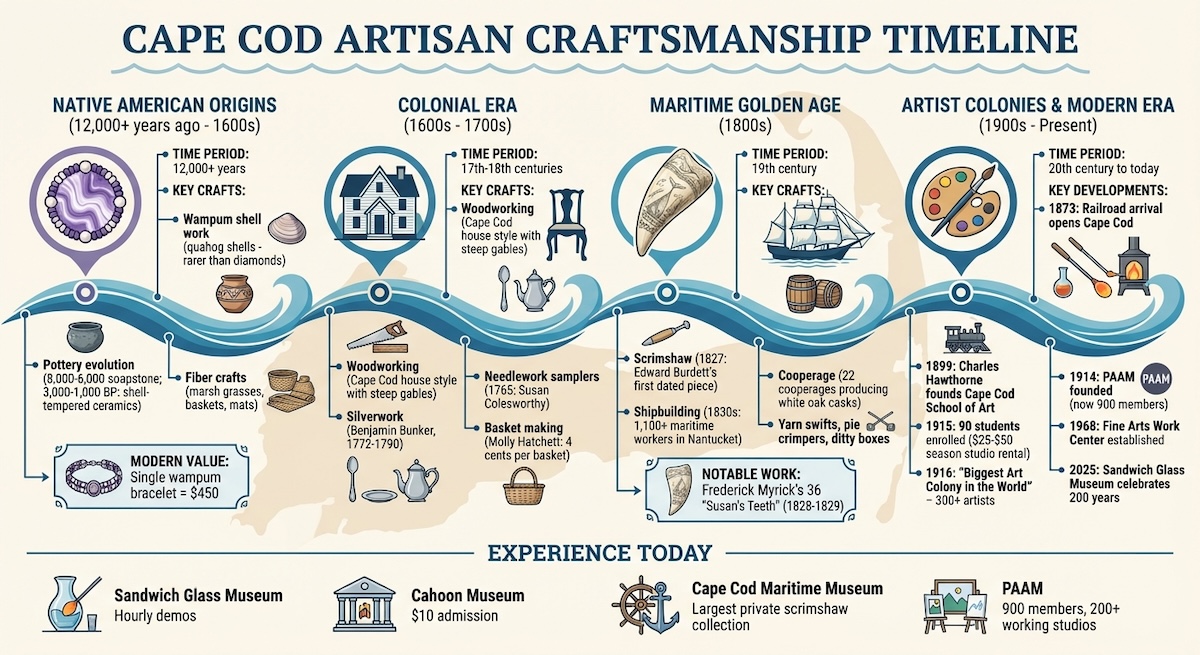

Cape Cod's artisan history spans over 12,000 years, blending Native American ingenuity, colonial-era functionality, and maritime artistry. From Wampanoag wampum jewelry to colonial woodworking and 19th-century scrimshaw, each era left behind a legacy of practical and decorative craftsmanship. Today, this heritage thrives in local museums, galleries, and workshops, showcasing pottery, woodworking, and maritime-inspired art. Highlights include:

Visitors can explore this rich history at venues like the Sandwich Glass Museum, the Cahoon Museum of American Art, and the Cape Cod Maritime Museum. These sites offer hands-on experiences, live demonstrations, and rare artifacts that connect past craftsmanship to modern artistry.

For over 12,000 years, the Wampanoag people have been shaping Cape Cod’s artistic heritage, long before European settlers arrived [7]. Their craftsmanship wasn’t just about creating objects - it was deeply tied to survival, community, and a spiritual bond with the land and sea. Among their many contributions, the tradition of wampum shell work stands out as a cornerstone of this legacy.

Wampum shell work is one of the most enduring symbols of Wampanoag artistry. Using quahog shells native to the region, they crafted beads and jewelry that carried immense cultural meaning. The deep purple core of quahog shells found in Cape Cod’s southeastern waters is exceptionally rare - rarer, even, than diamonds [6]. As Marcus Hendricks, a Wampanoag and Nipmuc artisan, explains:

The best purple exists in the southeastern part of Massachusetts on the south side of Cape Cod... the prized color comes from the minerals in the mud where the shells grow [6].

Wampum wasn’t just decorative; it held significant social and ceremonial value. When a tribal leader raised wampum during gatherings, it symbolized respect and the collective strength of the community.

The Wampanoag’s craftsmanship extended far beyond shell work. Pottery, for example, underwent significant evolution over thousands of years. Early examples from the Middle Archaic period (8,000–6,000 BP) were carved from soapstone, while later pieces from the Woodland Period (3,000–1,000 BP) featured intricate designs on finely crafted, shell-tempered ceramics [9]. Women, who were responsible for much of the community’s food production, played a crucial role in this craft. They sourced clay from places like Martha’s Vineyard and Nantucket, shaping it into vessels that were both functional and ceremonial [7][8].

The Wampanoag were equally skilled in working with natural fibers. They transformed marsh grasses, sedge, reeds, and rushes into essential items like mats, cordage, baskets, and coverings for their homes [8][11]. This work required not only technical skill but also a deep understanding of the local environment - knowing when to harvest materials and how to ensure their creations were both durable and practical.

Today, contemporary Wampanoag artists like Elizabeth James-Perry continue to honor these traditions. Speaking about her work, she says:

When folks wear my jewelry, I want them to get a sense of being involved in the story of the piece... That helps support Native culture, continuance and traditional values [11].

A single handcrafted wampum bracelet, showcasing the distinctive purple marbling of quahog shells, can sell for around $450 [6]. This enduring artistry not only reflects the Wampanoag’s rich history but also demonstrates how their traditions remain vibrant and relevant today.

When European settlers arrived on Cape Cod, survival required practical skills that would later evolve into trades defining colonial New England's character. Spinning and weaving were essential for creating clothing and bedding, while cooperage - the craft of barrel making - was vital for storing and trading goods [12]. These crafts weren’t about aesthetics; they were the backbone of everyday life in a challenging, resource-driven environment. Over time, these practical skills laid the groundwork for more specialized trades that became central to the region's identity.

Woodworking played a key role in shaping both homes and household items. The well-known Cape Cod house style is a testament to colonial ingenuity, designed to endure the region's tough climate. Features like steep gables to handle heavy snow, large central chimneys for warmth, and shingle or clapboard siding to withstand coastal winds were hallmarks of this design [14]. Inside these homes, artisans such as Thomas Dennis elevated local timber into functional art, crafting intricately carved oak chests using traditional joinery techniques [16].

Silverwork emerged as both a trade and a symbol of economic growth. Craftsmen like Benjamin Bunker, active in the Nantucket and Cape area between 1772 and 1790, produced high-quality silver items such as porringers and canns (drinking vessels). These served practical purposes while also reflecting the rising affluence of the merchant class [5].

For young women, needlework became a means of education and self-expression. They created samplers featuring elaborate designs and moral lessons, showcasing their skills and the values they were expected to uphold [5]. One example is the "Fishing Lady" needlework picture, stitched in 1765 by thirteen-year-old Susan Colesworthy. This intricate pastoral scene, made with silk, wool, and linen, was part of the curriculum at Boston-area boarding schools [5]. These works weren’t just decorative; they prepared young women for the responsibilities of managing a colonial household.

Despite the focus on refined crafts, many essential trades were undervalued, particularly those practiced by Native Americans and marginalized workers. They excelled in basket making, chair bottoming, and broom making, using materials like ash, oak, and rush to create everyday items [13]. However, their contributions were often overlooked. For instance, Paugusett artisan Molly Hatchett earned just 4 cents for a basket, while Peter Salem was paid 20 cents for bottoming a chair in 1806 [13]. Historian Nan Wolverton highlights their impact:

Indians, in fact, helped to maintain the 'well-kept petticoat of New England society' with their baskets for keeping things orderly, their newly woven chair seats, their mats for wiping dirty feet, and their brooms for sweeping up [13].

The importance of these items is evident in records like an 1804 estate appraisal, which listed 13 baskets as essential tools for storing and transporting farm products [13].

The 19th century marked the height of Cape Cod's maritime economy, leaving behind a creative legacy that turned everyday tools into cherished works of folk art. For many mariners, the sea was more than just a workplace - it was a space for creativity. During long voyages, they crafted intricate pieces, while skilled tradesmen onshore built the vessels that made their journeys possible.

The whaling industry on Cape Cod and Nantucket fostered an entire network of specialized trades. By the 1830s, Nantucket's harbor was bustling with over 1,100 maritime workers. Shipwrights built agile whaleboats, 22 cooperages produced thousands of airtight white oak casks, and sailmakers perfected their craft through rigorous three-year apprenticeships, sewing more than 30 sails per ship [15]. Meanwhile, shipsmiths forged essential tools like harpoons and lances, completing the whalers' toolkit.

Whaling also gave rise to scrimshaw - the art of engraving whale teeth and bone. Herman Melville described it as:

lively sketches of whales and whaling-scenes, graven by the fishermen themselves on Sperm Whale-teeth... in the hours of ocean leisure [17].

This industry provided unique materials for scrimshanders, including sperm whale ivory (rarely longer than eight inches), walrus tusks (up to 27 inches), and baleen plates [17]. In 1827, Edward Burdett created the first dated American scrimshaw aboard the ship Origon of Fairhaven, Massachusetts [17]. Shortly after, between 1828 and 1829, Frederick Myrick produced at least 36 "Susan’s Teeth", becoming the first scrimshander to sign and date his work while aboard the ship Susan [17].

Whalers crafted more than just art - they made practical tools and keepsakes. Items like yarn swifts (collapsible yarn winders considered marvels of scrimshaw craftsmanship), pie crimpers with ornate handles, carved canes, and ditty boxes were common [17][19]. Between 1853 and 1856, Captain James Archer used his spare time on a low-yield voyage aboard the bark Afton to craft an elaborate inlaid dressing case of wood, ivory, and glass for his wife Mary [5].

The creativity sailors developed at sea naturally transitioned into a unique folk art tradition when they returned home.

Many maritime artisans brought their skills ashore, becoming folk artists who carried forward the ingenuity honed during their voyages. Shadrach Gifford, once the first mate aboard the ship Hercules, created an intricate inlaid center table in 1852. It featured 1,384 pieces of veneer crafted from various woods, including peachwood from his own yard [5]. Similarly, Benjamin Russell (1804–1885), a former boatsteerer, gained fame for his ship portraits and his "Panorama of a Whaling Voyage 'Round the World" [18].

This folk art tradition was so widespread that whaleman John Martin, aboard the ship Lucy Ann, wrote in his 1844 journal:

there were enough canes in this ship to supply all the old men in Wilmington [17].

These self-taught craftsmen used inventive techniques, darkening engraved lines with lampblack (carbon from oil lamps) and incorporating materials like tropical woods, tortoise shell, and mother-of-pearl [17][19]. Their work often featured ship portraits, whaling scenes, and patriotic symbols like eagles and the American flag, serving as visual records of their maritime experiences. This transformation from functional maritime tools to folk artistry reflects Cape Cod's enduring ability to blend creativity with tradition.

The arrival of the railroad in 1873 changed everything for Cape Cod. Once a remote maritime community, it became an easily accessible retreat for artists, drawn not just by convenience but by the stunning coastal light of the Outer Cape, which provided an extraordinary clarity for their work [21][22]. By the early 1900s, Provincetown had become a hub for creative individuals looking for both solitude and a sense of community.

In 1899, Charles Webster Hawthorne founded the Cape Cod School of Art, encouraging students to approach painting in a fresh way. His advice to students was simple yet profound:

Don't think of things as objects, think of them as spots of color coming one against another [22].

By 1915, the school was thriving, with 90 students enrolled. At the time, boarding houses charged just 50 cents per night, and studio rentals ranged from $25 to $50 for the season [23][22]. Provincetown’s reputation grew rapidly, and by 1916, the Boston Globe declared it the "Biggest Art Colony in the World", boasting over 300 artists and students in residence [21][23].

World War I brought a wave of American expatriates back from Paris, and with them came European modernist movements like Cubism and Fauvism [22][23]. Hans Hofmann's Summer School of Art became a cornerstone of the region’s artistic identity, attracting students who later shaped Abstract Expressionism. Artist Myron Stout reflected on Hofmann’s teaching:

Hofmann was a rarity as a painter and a teacher. He knew where you were better than you knew it. Instead of pouring it in, he drew it out of you [22].

This artistic energy also influenced local craftsmanship. Take Ralph and Martha Cahoon, for example. Martha, who learned decorative furniture painting from her Swedish immigrant father, partnered with Ralph to create functional art like chests and trays. By 1953, with the guidance of patron Joan Whitney Payson, the Cahoons transitioned from functional pieces to framed folk art, making their whimsical "mermaids and sailors" scenes highly collectible [20]. Meanwhile, the Provincetown Printers pioneered the "white line" woodcut technique, using a single block instead of the multi-block method typical of Japanese woodcuts [21][23]. This evolution from practical crafts to artistic expression added another layer to Cape Cod’s rich maritime and colonial heritage.

As artistic traditions evolved, so did the drive to protect and celebrate them. Founded in 1914, the Provincetown Art Association and Museum (PAAM) became a vital link between the local community and the broader art world. Today, it boasts a membership of 900 [22][25]. During the Great Depression, the Works Progress Administration (WPA) provided opportunities for artists to stay on the Cape and continue their creative work [24].

By the 1960s, skyrocketing real estate prices threatened the artist community. To combat this, Robert Motherwell and Stanley Kunitz established the Fine Arts Work Center (FAWC) in 1968 with the goal of keeping artists in the area [22]. The FAWC continues this mission today, offering seven-month fellowships to 10 artists and 10 writers annually, ensuring that the creative energy of the colony remains alive [22]. Additionally, the Cahoon Museum of American Art, housed in a restored 1782 Crocker homestead, provides a space to explore the region’s artistic legacy. Admission is $10, with discounted rates of $8 for seniors and students, making it accessible for visitors [20].

These efforts have preserved Cape Cod’s unique blend of traditional craftsmanship and modern artistic innovation. The region’s native, colonial, and maritime influences remain alive through these initiatives. As PAAM CEO Christine M. McCarthy put it:

The magic of the landscape and the light draws you into this exquisite sliver of sand... the possibility of artistic immersion is at its height [21].

Cape Cod’s artisan heritage is alive and well, with museums and galleries offering a glimpse into centuries of craftsmanship. For a truly memorable experience, start with the Sandwich Glass Museum, which is celebrating 200 years of glassmaking in Sandwich in 2025 under the theme "Illuminating the Past, Sparking the Future" [27]. Here, you can catch hourly live glass-blowing demonstrations and even try your hand at creating your own glass keepsake during a "Glass Experience" session [27].

The Cahoon Museum of American Art is another must-visit. Located in the historic 1782 Crocker homestead, it showcases the whimsical works of Ralph and Martha Cahoon. Admission is $10, with discounted rates of $8 for seniors and students [20]. For maritime enthusiasts, the Cape Cod Maritime Museum offers a hands-on look at traditional wooden boatbuilding in its Cook Boat Shop. The museum also houses Cape Cod’s largest private scrimshaw collection, a testament to the region’s seafaring legacy [28].

The Falmouth Museums on the Green provide a fascinating dive into local history, featuring folk-art portraits and maritime artifacts. Don’t miss the "Faces of Change" exhibit, which displays ceramic mugs crafted by local students to honor historic figures [26]. Over at the Atwood Museum, visitors can explore the "Tool Room", filled with 19th-century trade artifacts, and marvel at the restored 150-year-old Atwood Store Sleigh [29]. For detailed schedules and more information, check out the Cape Cod Museum Trail website [30].

After soaking in Cape Cod’s artisan culture, why not pair your exploration with a luxurious stay nearby?

For a perfect balance of history and indulgence, consider staying at A Little Inn on Pleasant Bay. Located near Chatham, Harwich, and Orleans, this charming inn offers easy access to Cape Cod’s top craft museums and galleries. A scenic drive along the historic "Old King’s Highway" (Route 6A) will take you to the Sandwich Glass Museum, passing by centuries-old homes and artisan workshops along the way [31][30].

The inn’s nine uniquely styled rooms combine antique-inspired decor with modern comforts, capturing the essence of New England charm. Each room is thoughtfully designed to reflect the area’s rich artistic traditions. After a day exploring historic landmarks like the Wing Fort House or the Sturgis Library - the oldest library building in the U.S. - you can unwind with upscale amenities like private spa bathrooms, a European-style breakfast, and even a private dock for kayaking or sailing [31].

The inn’s concierge can also help plan heritage tours to nearby Brewster, where you’ll find the Sydenstricker Galleries showcasing exquisite glass art crafted on Cape Cod. Or head to the Osterville Historical Museum to see a stunning collection of full-sized wooden Crosby boats, an enduring symbol of Cape Cod’s craftsmanship [32][30]. Combining refined accommodations with proximity to artisan heritage sites, A Little Inn on Pleasant Bay offers the ideal retreat for those looking to immerse themselves in the region’s creative spirit while enjoying modern luxury.

For over 10,000 years, artisans of Cape Cod have left their mark, shaping the region's identity through creativity and craftsmanship. From the intricate marsh grass baskets woven by Native Americans to the iconic Cape Cod House introduced by colonial settlers, and the maritime artistry of scrimshaw and lightship baskets, each era has contributed to a rich cultural tapestry [10][8][3][4].

By the late 19th century, artists like Charles Hawthorne brought a new wave of creativity, founding the Cape Cod School of Art in 1899 and establishing Provincetown as America's oldest continuous art colony [1][34]. Today, this legacy thrives in the Cape's vibrant cultural districts, home to around 200 working artist studios [1][2][3].

This connection to the past isn't confined to history books. As Francis P. McManamon, Chief Archeologist for the National Park Service, explains:

The interpretation of ancient and historic activities at these sites provides a view of human uses of the Cape Cod coastline from earliest times. [10]

Visitors can immerse themselves in this living history through experiences like watching live glassblowing, exploring maritime artifacts, or visiting historic landmarks. These hands-on encounters not only preserve the stories of the past but also support the communities that keep Cape Cod's creative traditions alive [33][5].

Whether you're marveling at ancient shell piles once described by Thoreau or witnessing the work of modern artisans in their woodland studios, Cape Cod's legacy of craftsmanship endures. It’s a place where heritage and innovation intertwine, shaped by the timeless forces of sea, sand, and light [10][1]. This harmony between tradition and creativity continues to define the Cape's unique artistic spirit.

The Wampanoag people have kept their heritage alive through craftsmanship that reflects a deep bond with nature. Among their most iconic creations is wampum - beads meticulously crafted from quahog and whelk shells. These beads are often woven into belts and jewelry, serving as records of histories, treaties, and spiritual narratives. Another treasured tradition is scrimshaw, where intricate carvings on whale bone or ivory carry family stories and customs across generations.

The artistry doesn't stop there. The Wampanoag excel in twined basketry, quillwork, and woven sashes, blending natural fibers with intricate stitching to produce items that are both practical and decorative. They also work with materials like deerskin, clay, and copper, creating garments, vessels, and ornamental cuffs that embody their cultural ties to the land and sea of Cape Cod. These traditional crafts not only honor tribal identity but also adapt to remain meaningful in today's world.

Cape Cod’s deep maritime roots have profoundly influenced its craft traditions, seamlessly blending utility with creativity. During the height of the region’s fishing and whaling industries, there was a constant need for skilled artisans to support shipbuilding efforts. Shipbuilders and carpenters worked tirelessly to construct hulls, masts, and other vital components, showcasing their expertise in woodworking. This craftsmanship didn’t stop at the shipyards - it extended into everyday life, shaping the design and production of furniture and wooden household items.

The maritime economy also spurred the development of cooperage, where craftspeople specialized in making airtight barrels and casks to store and transport whale oil, fish, and other goods. Rope-making emerged as another essential trade, with workers twisting hemp into durable ropes for ship rigging. Over time, these practical skills evolved into decorative art forms, giving rise to traditions like scrimshaw, intricately carved wooden trinkets, and nautical-inspired jewelry. These creations continue to celebrate Cape Cod’s lasting bond with the sea.

Artist colonies, such as the Provincetown Art Colony established in 1899, played a crucial role in keeping Cape Cod's craft traditions alive. These communities became hubs for painters, sculptors, woodworkers, and textile artists, fostering an environment where skills were exchanged, native materials like local woods and hand-dyed yarns were embraced, and craftsmanship thrived.

With exhibitions and organizations like the Provincetown Art Association and Museum, these colonies not only highlighted local talent but also gave Cape Cod’s artisanal heritage a broader cultural importance. Efforts like the Federal Art Project of the 1930s brought national recognition, ensuring that Cape Cod’s crafts earned a lasting place in the story of American art.

If you're looking for a peaceful and personal Cape Cod experience, now's the time to book your stay at A Little Inn on Pleasant Bay. With its quiet setting, friendly hosts, and small seasonal touches that make a big difference, it’s a great place to relax and enjoy the best bed and breakfast in Cape Cod. Whether you’re planning a weekend getaway or a longer break, don’t wait too long—anytime is the best time to visit, and rooms fill up fast.